# Image FEC

Learning state representations from images

@hmallen @QuantumJuker @cwbeitel

# Summary

So far here we focused on reproducing Vemulapalli and Agarwala (2019; with good results) then used the trained model for real-time state feedback during meditation exercises. It looks like we can attain an improvement both by improving the loss to include a little self-supervision as well as by just doing a fair amount more tuning (the demo version was nearly the first configuration we tried).

# Datasets

The FEC dataset consists of around 500k face image triplets (derived from 156k images; see Table 1) along with annotation of which pair within the triplet are most visually similar in terms of facial expression at the exclusion of factors such as identity, gender, ethnicity, pose age, etc. (as assigned by multiple human annotators - six for the majority of the dataset). Triplets are also annotated according to how far different they are expected to be based on semantic expression labels (obtained by the authors separately and not distributed). These labels include Amusement, Anger, Awe, Boredom, Concentration, Confusion, Contemplation, Contempt, Contentment, Desire, Disappointment, Disgust, Distress, Doubt, Ecstasy, Elation, Embarrassment, Fear, Interest, Love, Neutral, Pain, Pride, Realization, Relief, Sadness, Shame, Surprise, Sympathy, Triumph. A one-class triplet is one where all three share a label in common; a two-class triplet is one where at most two share a label in common; and a three class triplet is one where none share a label. The dataset consists of such annotations, the URL of the publicly-available source image (primarily Flickr), and bounding boxes for the region within the source image where the annotated face image can be found.

For each triplet in the dataset, the download of each image was attempted and if successful filtered according to whether a face was present at the expected bounding box coordinates. Face detection was performed using Faced (https://github.com/iitzco/faced) which employs deep CNN’s, one stage of which includes a network based on YOLOv3 (Redmon and Farhadi, 2018), for fast face detection on CPUs. Images are first cropped to bounds provided by FEC (expanded by 15% along each axis) the result of which was passed to Faced for face detection and subsequent filtering on that basis. All images were then standardized to a size of 128px preserving aspect ratios and padding with gaussian noise.

The VGGFace2 dataset (Cao, et al., 2018) consists of 3.31M images from 9,131 individuals obtained via Google Image Search. These images span a wide variation in pose, age, illumination, and vocation. Naturally, the dataset is biased in abundance towards existing bias in the distribution of celebrities and public figures such as in terms of ethnicity and vocation. The gender balance of the dataset is 59.3% / 40.7% male/female. The dataset was designed to include a large number of images per identity with the min, mean, and max of these being 80, 362.6, and 843, respectively. Automated annotations include facial bounding boxes, facial keypoints, and age and pose predictions. Identity annotations were a mixture of initial search according to KnowledgeGraph name queries followed by filtering performed by human labelers on the basis of whether at least 90% of the images in an identity class were from the same individual.

# Methods

# Vision networks

Networks for processing images were in all cases based passing the output of ResNet-50 into a series of fully connected layers (interspersed with ReLU activations) and ultimately L2 normalization to produce the output embedding.

# Augmentation

Standard image augmentation techniques were applied including random cropping (randomly ~15% by area), horizontal flipping (p=0.5), and jittering of brightness and contrast (+/-10%).

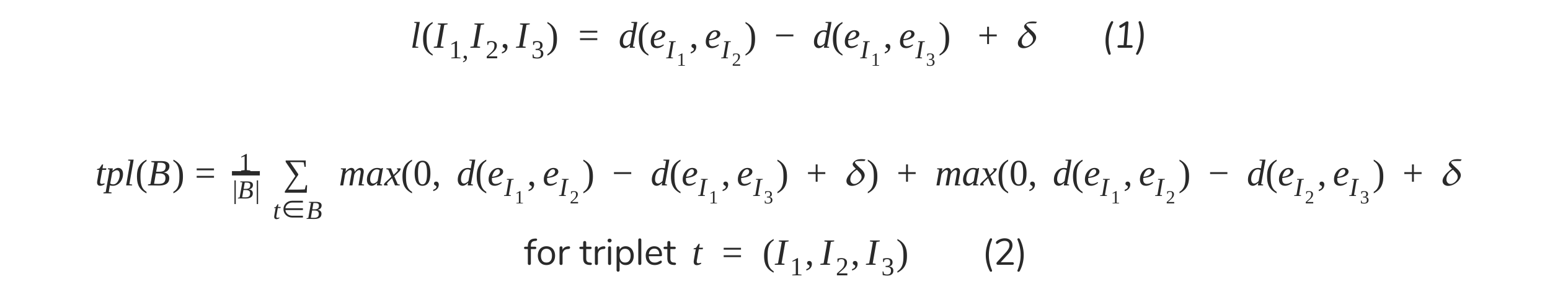

# Triplet distance loss

For training on both the FEC expression similarity problem and pre-training on the VGGFace2 identity problem we use the triplet loss (1) advocated by Schroff, Kalenichenko, and Philbin (2015), reformulated by Agarwala and Vemulapalli (2019) to consider either I_1 or I_2 as anchor points (2), both encouraging the distance between positive pairs to be less than negative ones. The training time loss for SGD is computed in the standard way as the sum of the element-wise losses over the batch normalized by the batch size.

To avoid repeating ourselves the triplet loss formulae are these and further discussion is available in the original whitepaper (here) or the UM EEG SSL design doc:

# Embedding consistency learning

We are interested to extend this with an embedding consistency loss term that provides additional unimodal self-supervision in the form introduced by Qizhe, et al. (2019; “unsupervised data augmentation” or, here, UDA). Here, an image I is differentially (randomly) augmented in two ways, giving I'and I'', the distance between the embeddings of these is sought to be minimized over batch B, uda(B)=1|B|IBd(eI',eI'').

# Pre-training on VGGFace2

Prior to training on the problem of facial expression correspondence, for which a comparatively much smaller dataset is available, networks were pre-trained in the style of FaceNet (and related) on the problem of identity understanding using the triplet embedding loss discussed above. Here l(I1,I2,I3) refers to I1 and I2 being images from the same person and I3 being an image from a person of a different identity.

# Learning facial expression correspondence

Training on facial expression correspondence was performed using examples from the FEC dataset based on pre-training on the aforementioned identity learning problem using the VGGFace2 dataset. In this case, the same triplet distance loss was used but here l(I1,I2,I3) refers to I1 and I2 being images human raters considered to be more similar in expression than either of those compared to I3. In contrast to the approach described in Vemulapalli and Agarwala (2019) we used the same 𝛿 margin of 0.1 for each of the triplet types and do not balance triplet types within batches.

# Quantitative metrics

Triplet embedding accuracy (4) was computed in the way described in Vemulapalli and Agarwala (2019),

tpa(B)=1|B|tB( d(eI1,eI2) d(eI1,eI3) ) & ( d(eI1,eI2) d(eI2,eI3) ) for triplet t = (I1,I2,I3) (4) TODO: Markdown display of image FEC tpa metric.

where T is a collection of triplets, |T| is the size of that collection, and where d(ei,ej) is the l2distance used in training.

# Qualitative analysis

Qualitative analysis was performed in the way described by Vemulapalli and Agarwala (2019) where query/result pairs were produced by obtaining an embedding for a query image then adjacently displaying other images nearby in embedding space (in rank order by increasing distance).

More formally, a sample of 2,000 training set images were embedded by the model and processed for k-nearest-neighbors lookup using sklearn.neighbors.KDTree using a leaf size of 4 and the Euclidean metric. Search was performed with a k of 4 using an image from the evaluation set (not included in training). Query/result sets were filtered according to those where the top-ranked result had a distance of at most 1.77 as well as to omit images for the protection of the pictured (on account of apparent age or emotion expressed, e.g. malice).

Naturally populating the search space with only 2k images will tend to yield results of lower quality than one with 10 or 100 times that (which is a key next step).

# Experiments

TODO: Include new results once we finish the new implementation using Trax presumably matching results from the original whitepaper.

- How did we do in terms of TPA?

- Do models with significantl different TPA seem to give significantly different qualitative results?

- How useful was UDA?

# Qualitative analysis

TODO: Include image examples

The results look quite good.

In some cases, several copies of the same image will be returned as results for the same query. This is due to embeddings for these being computed on the augmented forms of the images. Relatedly, in some cases a query image will return an identical image as a top-ranked result but with non-zero distance. One point is that we would prefer embeddings to be invariant to augmentation so that when models are used in production their representations are invariant to dynamical changes in lighting, for example.

This is also relevant for specifying (and cueing for) goals that are similarly independent of various dimensions of augmentation. Such invariance is likely obtainable by including the UDA loss component discussed above.

Another key issue raised by these observations is that while the triplets present in the training and eval sets may be disjoint, it appears the primary images are not. Thus an important next step is to construct a query set by cross-referencing the source image URLs of potential queries and those for images used in training.

# Demos

All of these involve obtaining images from a user's webcam, embedding them with a locally-served version of the model (currently singular) described above and providing tonal feedback on the basis of the distance of one's current state embedding from an embedding of a previously-specified goal state.

# References

Xie, Qizhe, et al. "Unsupervised data augmentation." arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.12848 (2019).

Schroff, Florian, Dmitry Kalenichenko, and James Philbin. "Facenet: A unified embedding for face recognition and clustering." Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2015.

Vemulapalli, Raviteja, and Aseem Agarwala. "A Compact Embedding for Facial Expression Similarity." Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2019.